Sumatran tigers (Panthera tigris sumatrae) are a critically endangered tiger subspecies native to the Indonesian island of Sumatra. They are one of the smallest tiger subspecies and are distinguished by their thick black stripes and dark orange fur.

The Sumatran tiger is the only surviving tiger population in the Sunda Islands, where the Bali and Javan tigers are already extinct. The current population is estimated at around 400 to 600 individuals, but these numbers are uncertain due to the difficulty of tracking in their dense forest habitats. They reside primarily in the island's remaining patches of dense forest and are heavily dependent on these forest ecosystems for hunting and shelter.

Sumatran tigers are threatened by habitat loss, poaching and human-wildlife conflict, which often occurs near villages and plantations, leading to fatalities on both sides, which can prompt retaliatory killings of tigers.

The survival of the Sumatran tiger is crucial for maintaining the ecological balance and biodiversity of Sumatra’s forests.Involving Indigenous peoples in the protection of the Sumatran tiger is essential for several reasons, reflecting their unique position, knowledge, and relationship with their local environment.

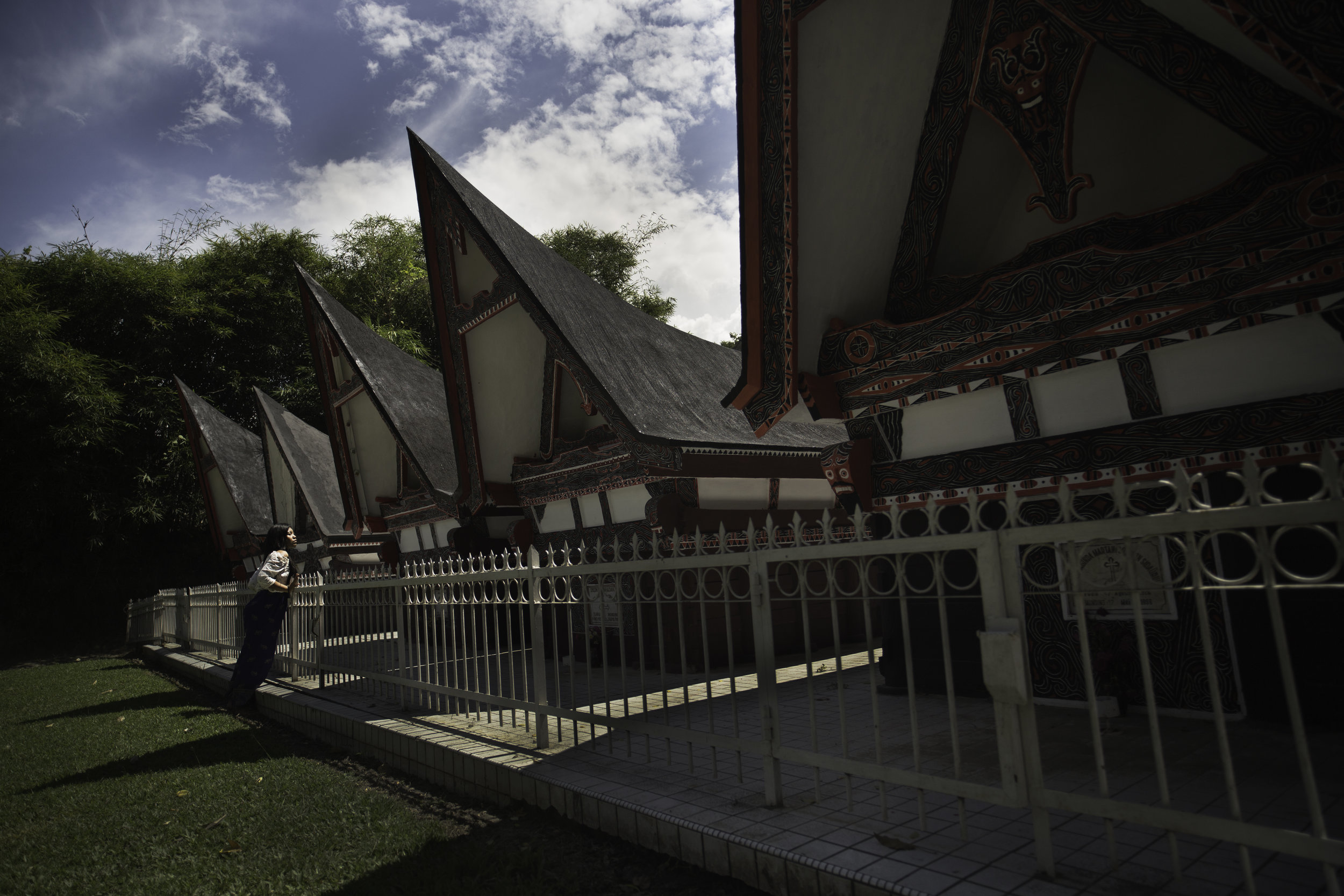

I recently completed a short documentary funded by National Geographic Society featuring a Batak conservationist in Sumatra named Nayla Azmi where we explored the topic of Indigenous feminism in Sumatra.

For many Indigenous communities, such as the Batak, the tiger holds significant cultural and spiritual value. They see tiger as “Opung,” which means “grandparent” or “ancestor.” They are a symbol of the forest’s health and a guardian spirit known to in many stories to have connections to their earliest clan ancestors.

The Batak and other local Indigenous groups possess extensive knowledge of their local ecosystems, including the behavior of the tigers and the dynamics of the forest. This traditional ecological knowledge is invaluable for developing effective conservation strategies that are tailored to local conditions. Such knowledge includes understanding migration patterns, the location of critical habitats, and the ecological roles of various species within the forest.These communities typically engage in sustainable land-use practices that have allowed them to coexist with wildlife over centuries. Their approaches to managing resources often promote biodiversity and ecological health, which are essential for the habitat of the Sumatran tiger.

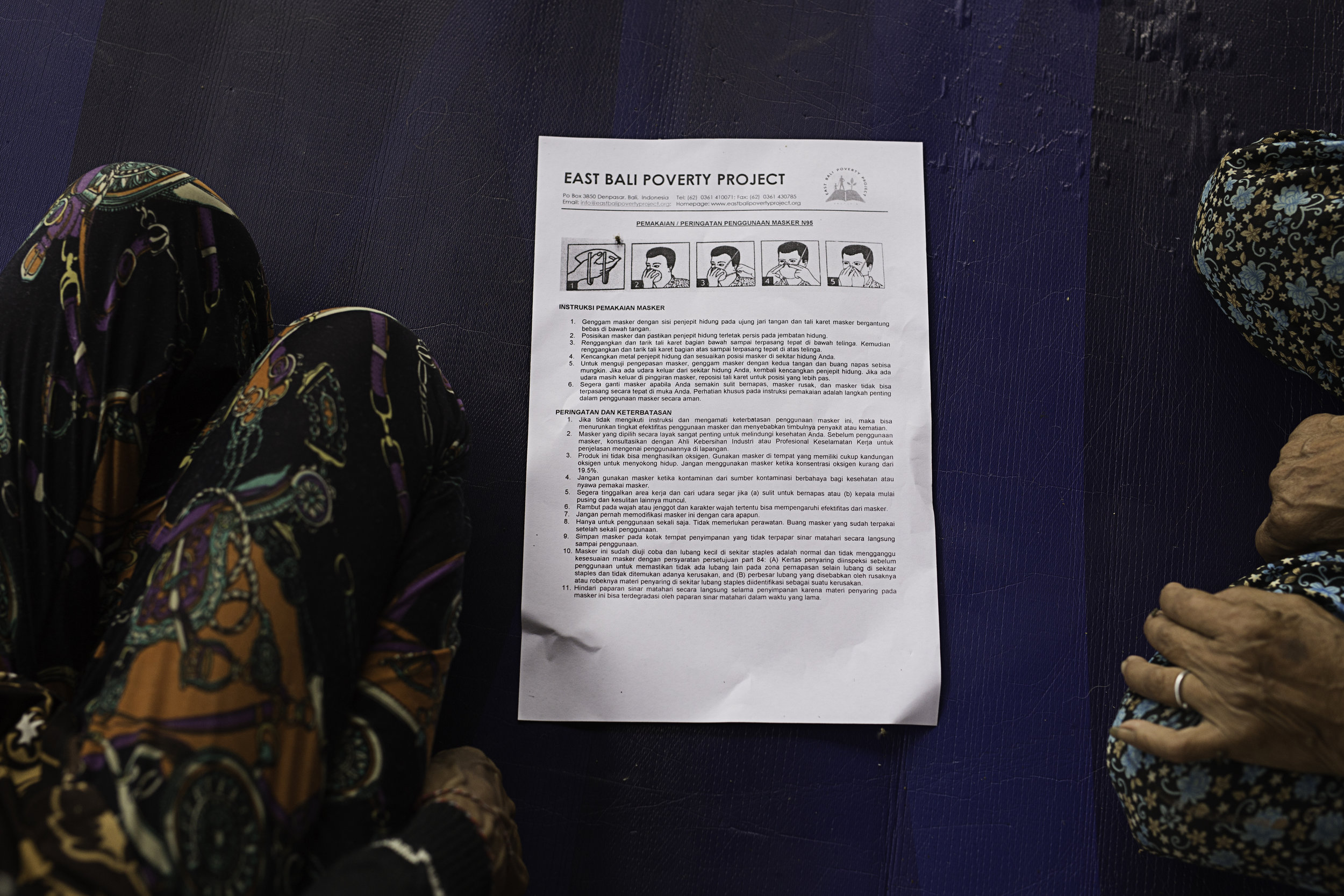

When Indigenous communities are involved in conservation efforts, they are more likely to take stewardship roles in protecting the wildlife and the forests, which can foster a sense of responsibility and pride in conservation outcomes.It can also lead to more effective monitoring and enforcement of conservation laws. Indigenous peoples can serve as the eyes and ears on the ground, helping to detect and deter poaching activities and other illegal activities that threaten tigers and their habitat. Also, potential conflicts between humans and tigers can be better managed. Indigenous peoples can help implement and advise on conflict mitigation strategies that are respectful to both the wildlife and human needs. In addition, socioeconomic benefits, such as job creation can lead to improvements in local livelihoods. This, in turn, reduces the economic pressures that might otherwise lead communities to resort to deforestation or poaching.

Above all, it is perhaps the intergenerational healing that results for Indigenous communities when being reconnected to their land and their ancestors that is most important. After enduring a brutal genocide at the hands of the Dutch colonists, as well as the destruction of the land through the introduction of African palm oil, rematriation seems like a crucial step towards collective liberation.

I am hopeful that the documentary we created and accompanying images will position Nayla and her all-Indigenous female ranger team as local conservation “heroes,” and that I will add something to the fabric of validating traditional ecological knowledge and Indigenous ontologies in science and conservation spaces.